She recalls her husband – an illiterate man who signed with his thumb impression – didn’t know much about Covid-19 but knew well enough that he was gravely ill. Drifting for days between poorly resourced community health clinics and government-run Covid-19 treatment centres, Ramling’s health deteriorated. After almost a week of being ill, he finally managed to find himself a bed at Deep Hospital in Beed district, a multi-storey private facility.

Piecing together information from daily phone calls with her husband, Rajubai says five days into his treatment, which included the provision of intermittent oxygen and medications unknown to either of them, hospital authorities demanded Ramling pay another USD 1,900 before they considered discharging him.

“I was married when I was my daughter’s age. My father married me off so he would have one less mouth to feed,” recalls Rajubai. And having married their eldest daughter off at 16, Rajubai and her husband vowed to break this generational cycle of poverty and have their second daughter Sona finish school.

Until Covid-19 decimated this family, that dream was a daily, but plausible, struggle. To raise a daughter to stand on her own feet with an education that could lift her out of poverty is now an even bigger challenge for Rajubai but her resolve is stronger than ever. Tragedy has sparked this woman’s fire and she’s committed to making her dead husband’s big wish come true.

Just months ago, their gods failed them, taking from them the one thing they loved most in the world: their Baba.

In the world where Rajubai now lives, emergencies are death sentences and she’s had one too many. She can’t farm the family’s little patch of land where they grow soybean and onions and work as a labourer at the same time, reducing her earning potential and the financial resources she needs to pay off the family’s seemingly insurmountable debt and educate her children. Local contractors and factories only employ married couples to work as teams, one of the region’s mainstay crops; widows, Raju Bai says, aren’t hired. “We were always poor but when Ramling was alive we never felt it. Now we feel the pinch,” she explains. Rajubai describes crippling leg and back pain from hours upon hours of standing, bending and toiling. But come rain, hail or shine she has to do it, because to not would mean to starve.

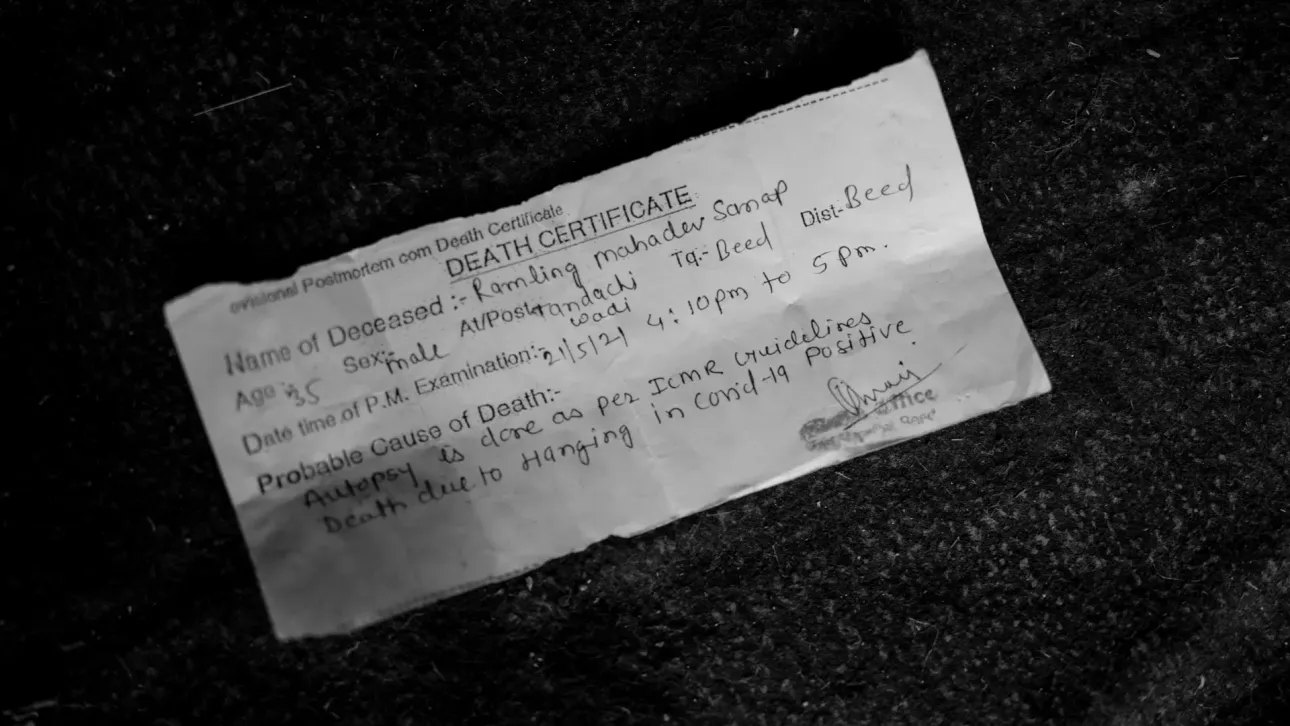

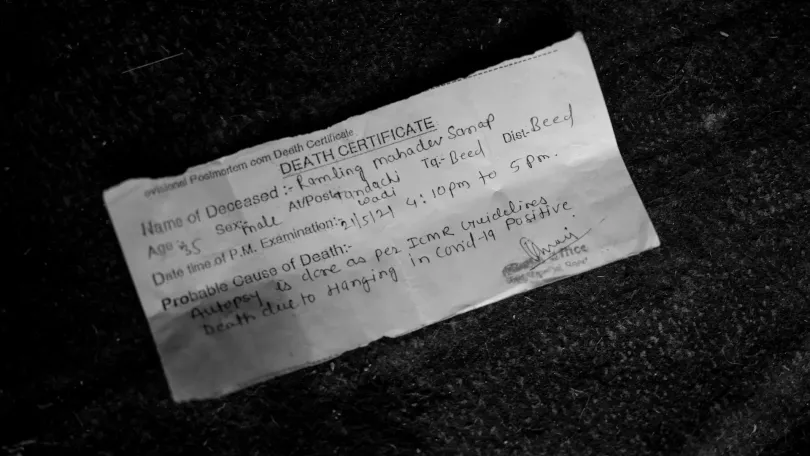

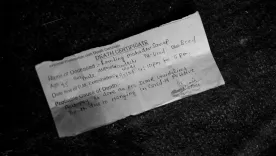

Rajubai says her husband’s body was removed and sent to a government facility before she could get to the hospital. Hours later, after what she describes as a rushed post mortem, the local police allowed Rajubai and her brother to watch his cremation on the banks of a local river. It was all too sudden, she laments, the memories of that day are a horrible blur.

A victim of India’s second Covid-19 wave, which by May had officially killed nearly 100,000 people in Maharashtra alone, farmer and daily wage labourer Ramling became infected with the virus after visiting a nearby town for work. With his health faltering, Rajubai says her husband hopped on his motorbike and went in search of medical attention.

“My kids don’t have a father now, I am their mother and father. And if I decide to educate them then it’s me who’s going to do it. That’s the reason I have made myself strong. There is no one to help me… I will do everything it takes,” says Rajubai.

Around 10pm that night, her husband called to ask how she and the kids were doing and whether the money had been arranged. The couple spoke in an upbeat tone of plans for his isolation when he returned home and managing the financial strain.

Covid-19 has pushed Rajubai to the edge where she is forced to make big life decisions every day: to send her children to school or have them help on the farm, to sell the little jewellery she has left to pay for medical care for her sick son or hope that his bout of typhoid passess with the few medicines she can find cheaply.

“I told him not to worry and that we’d sell our land if we had to in order to afford his treatment,” says Rajubai.

“He was a good man, a healthy man who never acted out of character. Why did he do it then?” Rajubai asks out loud, her stoic eyes welling with tears. A woman on a mission, she wants answers and justice. With the help of her brother, Rajubai tried to file an incident report against the hospital with the local police. When her attempts were rebuffed, she says she wrote to the superintendent of police who, she claims, did little more than try to persuade her to withdraw her complaint and broker a financial settlement with the hospital – an offer Rajubai refused.

In their small village hamlet of Tandalyachiwadi in Beed district in the western Indian state of Maharashtra, excitement builds for Ganesh Chathurti, the annual festival of the Hindu elephant god. But as their neighbours prepare to celebrate the generosity of this portly god of good fortune, Sona, 15, and Chaitanya, 11, stare vacantly from the doorway of their modest two-room home.

They eat in silence because that’s all that’s left. Since Covid-19 claimed their father Ramling Sanap in May 2021, words have failed this family of three. Theirs isn’t just a story of a family in mourning; it’s one of broken healthcare infrastructure and a corrupt and inept justice system. Rajubai’s tale is the real life manifestation of what happens when tragedy strikes at the bottom of India’s social and economic pyramid and how it disproportionately affects women and their ability to not only survive, but also thrive, in the aftermath.

Rajubai says in the hours after their brief exchange, Ramling tied his gamcha, a traditional thin scarf, around his neck and hung himself from a metal grill in the stairwell of the hospital. He was 38.

Despite what she’s been through, Rajubai doesn’t have the luxury of dwelling on anger, bitterness or self-pity. It’s fair to say she doesn’t expect anything from a system that’s given her nothing to begin with. Any justice for Ramling is an unaccounted bonus and one that will, if ever, come in the distant future.

As dusk falls, dance music blares from speakers, disco lights flash around a dancing mob and worshippers load decorated statues of Lord Ganesh onto trucks en route to immersion activities at the nearby river. In the shadows of this religious euphoria, Rajubai prepares a scant evening meal of rotis and forest leaves that she and her children foraged on their way home from their farm.

Breathless and in need of urgent care, Ramling checked himself in on May 13. Rajubai says they cobbled together around USD 2,300 for the hospital deposit, a crippling financial blow for the couple who were already struggling to repay loans they’d taken to marry off their eldest daughter a year earlier. But what’s money when it comes to saving a loved one, she laments.

What Rajubai holds in abundance is the quiet fortitude to persist despite the odds. Where does she get the courage? I ask. “What courage do I have?,” she says. “We fold our hands in front of god. We get to work and eat and I am thankful for that. I pray to god to look after us. It’s his decision to keep us alive or dead. That’s what I say to myself and move ahead.